Niguma, Lady of Illusion donne un rare aperçu de l’histoire du bouddhisme féminin. Il s’agit de la vie et des enseignements d’une femme mystérieuse vivant au onzième siècle au Cachemire, qui est à l’origine d’une lignée majeure du bouddhisme tibétain. Les circonstances de sa vie et les qualités extraordinaires qu’on lui lui prêtait sont analysées dans la perspective de la doctrine bouddhiste. Plus qu’une présentation historique, Niguma soulève la question des femmes en tant que chefs spirituels réels par rapport aux images masculines du «principe féminin».

Niguma, Lady of Illusion donne un rare aperçu de l’histoire du bouddhisme féminin. Il s’agit de la vie et des enseignements d’une femme mystérieuse vivant au onzième siècle au Cachemire, qui est à l’origine d’une lignée majeure du bouddhisme tibétain. Les circonstances de sa vie et les qualités extraordinaires qu’on lui lui prêtait sont analysées dans la perspective de la doctrine bouddhiste. Plus qu’une présentation historique, Niguma soulève la question des femmes en tant que chefs spirituels réels par rapport aux images masculines du «principe féminin».

Ce livre comprend les treize textes attribués à Niguma dans le canon du bouddhisme tibétain. Ces oeuvres réunies forment la base d’une ancienne lignée, Shangpa, qui continue d’être activement étudiée et pratiquée aujourd’hui. Dans ces textes figurent la source de pratiques ésotériques comme les Six Yogas et le Grand Sceau ainsi que les pratiques tantriques Chakrasamvara et Hevajra qui sont largement répandues dans les traditions tibétaines. On y trouvera aussi les quelques éléments biographiques disponibles.

« Une figure historique féminine majeure comme Niguma a été voilée par des siècles de mythologie, mais désormais Sarah Harding a habilement réussi à séparer le bon grain de l’ivraie et à révéler quelque chose de la femme derrière la légende, avec sa place dans la tradition Shangpa et ses écrits fascinants sur le Yoga. » Jetsunma Tenzin Palmo

Niguma, Lady of Illusion: An Interview with Sarah Harding

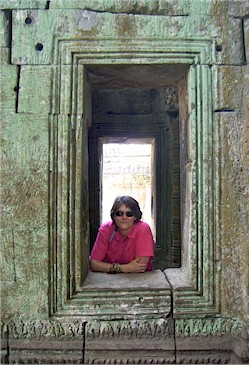

Sarah Harding is a lama in the Shangpa Kagyu tradition of Tibetan Buddhism, having completed the first three-year retreat for westerners in 1980 under H.E. Kalu Rinpoche. She now works as a teacher, oral interpreter and translator. Some of her translations include The Life and Revelations of Pema Lingpa and Machik’s Complete Explanation. She has been an instructor at Naropa University since 1992 and continues to teach her Tibetan Language Correspondence Course. Sarah is currently working on translations as a fellow of the Tsadra Foundation. Her next book is on the life and teachings of Niguma which form an important part of the Shangpa Kagyu lineage.

Jeff Cox: I would like to know more about your interest in dharma, your training, and how it brought you to this point of translating the teachings of Niguma.

Sarah Harding: It is a long, old story. I was propelled out of the country when I was 19. I went to Europe and then to more exotic places until I ended up in India and Nepal. During my travels in Nepal, I became aware of lamas giving teachings. Because I had already encountered Buddhism at UCLA, meeting Buddhism in Nepal wasn’t such a stretch for me. I did the 2nd and 4th courses at Kopan (around 1973). After one of those courses, someone showed me a photo of Kalu Rinpoche and that was it! I then found a way to go to Sonada in Darjeeling and as I got off the train, someone named Long Ron came right up to me and asked: « Do you want to meet Kalu Rinpoche? » The next thing I knew I was in his room and he was my teacher.

JC: So photos really do convey a lot of information!

SH: Yes, it was one of those classic hair-standing-on-end moments. The journey was arduous and I went straight as the crow flies (which you are not supposed to do) and from then on, I was in trouble with the Indian government. The monastery is in a restricted area—I took a Nepal airline flight into the middle of nowhere and at the border, the officials said I couldn’t go in. I started crying and they said: « Oh, you are a lady, we will let you go in. » Somehow from the moment I saw the photo, I knew I was going to meet my guru. It was a strange situation with Kalu Rinpoche because he looked so different, like an alien and yet so totally familiar. I never had a doubt about him being my teacher. I was lucky—I didn’t have to examine his qualities…I just knew he was the one to help me. I began doing the practices of the Shangpa lineage.

JC: When did you decide to do an extensive retreat?

SH: In 1974, a short time after I met Kalu Rinpoche, he asked me to help bring him to the USA. On that trip, he had the idea to offer a three-year retreat for westerners. I still remember clearly, it was at my father’s house in Los Angeles where he announced it. I knew immediately that I wanted to do it, but at first, he thought I was too inexperienced. It took a lot of persuading, but he finally agreed to allow me to be in the first retreat that would begin in 1976 and end in 1980. I began preparing by learning Tibetan and doing ngondro and other preparatory activities. I lived in a couple of other places before the retreat—Vancouver and also Seattle where I studied with the Sakya teacher Deshung Rinpoche, my second most favorite lama. Kalu Rinpoche would tell us that when he was away we should turn to Deshung Rinpoche. Many of Kalu Rinpoche’s students studied with Deshung Rinpoche. He regarded Kalu Rinpoche as his second root guru.

JC: Please tell me about the retreat. Was it a solitary or group retreat?

SH: It was a group retreat based on the Jamgon Kongtrul model that was developed at Palpung Monastery in Kham. We were in France at Kagyu Ling. There were seven women in one retreat place called Nigu Ling, and seven men in another place called Naro Ling. Lama Tenpa was our retreat master and there was a cook.

JC: When you first met Kalu Rinpoche, you had not been studying Tibetan had you?

SH: No I hadn’t been, but he had me studying the very next day! He gave me one of his lamas to begin teaching me Tibetan and in that first day I learned the alphabet and how to spell my name in Tibetan. Kalu Rinpoche felt it was important for people to learn Tibetan because it would lead to a deeper understanding of the dharma. That is why there are so many of his students that know Tibetan.

JC: Did he have a translator around him at that time?

SH: Yes, he had good translators at the time. It was a big inspiration for me to want to learn Tibetan so that I would be able to understand Kalu Rinpoche—that was my only motivation; I never planned to become a translator. I just wanted to understand him. Even with a good translator, it was unacceptable to me to have a mediator.

JC: Yes, I would think that it would be that way for you. It seems that you wouldn’t want anything between you and the source, be it Tibetans or Tibetan texts.

SH: Exactly, I feel that very strongly. On the other hand, I used to have profound moments with Kalu Rinpoche before we could speak with each other. There was no one around and we would be together in silence. Once I could speak, my discursive mind could not let that silence just be—I had many questions, and now I feel I might have been missing out on the real thing that was going on.

JC: Still, you experienced his depth. You really wanted to understand the dharma and wanted to study the texts in the original and come to your own conclusions without intermediaries.

SH: Every time I bump up against a dharma scene where there are various restrictions, I am so glad that I can go directly to the source and no one is blocking me. It skips a lot of bullshit.

JC: In a tradition where there are many rules that can prevent access by women because they are treated secondarily, I imagine that women have had a harder time accessing the teachings. They weren’t trained in philosophic Tibetan.

SH: I think that it is true that women did not receive the same training except in rare circumstances where by birth they were like royalty.

JC: You mean special cases like Jetsun Kushog who is Sakya Trizin’s sister, or Khandro Rinpoche who is Mindroling Rinpoche’s daughter?

SH: Yes, like that. From what I have seen in nunneries in Bhutan, the nuns don’t get the good teachers or training. There is not a huge bias, it is just that they are overlooked as far as training goes. And they very much want that training. I suspect it was like that in Tibet from everything I have read and heard.

JC: What have you translated so far?

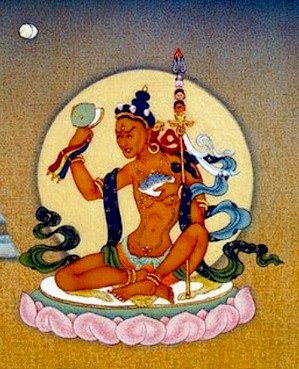

SH: I have done several books, not all by women by any means, but I am interested in women who bucked the system and have displayed their own agency. However, it is hard to find the actual historical women, because of the cultural overlays on the great women such as Machik and Niguma. In the case of Niguma, it is really difficult to find out about the person. Niguma did not have pen in hand to create the texts ascribed to her. Her disciple Khyungpo Naljor wrote everything down—it is not clear that he ever met her as a real person. It makes one wonder if she is a real person or just the imaginative mystical creation of a yogi. The text Stages of Illusion is attributed to her. It is a lengthy treatise, much more than just a few vajra lines. I like to think that the source of that teaching came from Niguma, but I can’t prove it. Everything attributed to Niguma was recorded by Khyungpo Naljor. Back in the 10th and 11th centuries the sources of other lineages such as Virupa didn’t write their teachings down either. In the case of Niguma, where Khyungpo Naljor is having mystical experiences of dakinis, it is hard to know if the dakini is a person or the yogi’s pin-up girl.

I have always been proud that the Shangpa lineage was founded by Niguma and Sukhasiddhi, but the question remains: Are they the actual women or the names for the inspiration of Khyungpo Naljor? We think that the presence in Tibetan culture of inspirational beings called dakinis somehow indicates that women are highly respected, but that is wishful thinking. Jose Cabezon has said: « Like the Trojan horse, beware of the patriarchy bearing symbols of the feminine. » I have spent some time investigating whether Machik and Niguma were the consorts of great men—revealing a cultural attitude that these women could not be great by themselves but only by association with men. In both cases there is no evidence that Machik was the consort of Dampa Sangye, as many Tibetans think, nor evidence that Niguma was Naropa’s consort. Our cultures seem to need to believe that powerful women became so because of powerful men.

JC: Because the Shangpa lineage had Niguma as a founder, do you think that there is greater respect in that lineage for women of wisdom?

SH: I do think it has had an effect. Once a woman is recognized as a dakini, there is no longer any question of respect for that person. Kalu Rinpoche was open to women practitioners receiving equal training. When plans for the three year retreats came up, I know that some of Rinpoche’s associate lamas were skeptical about the prospect of having a women’s retreat, but he did it anyway. He had confidence that the women were equally capable. But he also had limits. For instance calling women « lama » as a recognition for completing the three year retreat was difficult for him, but he didn’t have a problem calling the men « lama. » For him, it was like calling a woman « Mr. » All of us were considered capable of teaching after the retreat; he just didn’t want to call women « lama. »

JC: Chagdud Tulku impressed me because of the good training he gave to several students, including his wife and Lama Tsering Everest. He recognized them as capable teachers; they are now continuing his work after his death.

SH: Chagdud Tulku was very important for me having any confidence at all. I translated his written work and his oral teachings for a number of years—he had no issue about women at all. I would say he had more confidence in women than he did in men. He certainly had more confidence in me than I had in myself.

JC: We need our teachers to see our potential for growth and to relate to that.

SH: Women often have confidence issues, so for him to display confidence was huge for me. I was cleaning houses for a living, and when he heard that I had done the retreat, he was completely outraged and said « What are you doing! » He would always make sure I was paid for dharma work. Every interview I translated, he would give me half of the donation.

JC: How is the Shangpa lineage different from others?

SH: It stands out as a different lineage. According to Jamgon Kongtrul, the eight « practice » lineages derived directly from India. In the case of the Shangpa, Khyungpo Naljor received teachings from approximately 140 masters in India, and among them were Niguma and Sukhasiddhi. The Marpa Kagyu lineage received teachings from the Indians Maitripa and Naropa. The Tibetan lineages are traced to one person, usually, who received teachings from outside Tibet. Each lineage has different teaching emphases. For example, the yogas of Niguma are more straight-forward and simple than those of Naropa. In Shangpa, you are encouraged to visualize your root guru instead of Vajradhara. This indicates that the devotional aspect may be emphasized differently. Niguma’s « Stages of Illusion » understands the bodhisattva grounds and five paths as illusion. In my mind this seems particularly feminine. Niguma was a person who was hard to find—illusory in that sense. That ephemeral quality is the very definition of dakini. It was important to her that we don’t take everything so literally, solidly. Most of the teachings on the paths and grounds are incredibly fixed and detailed as to what happens at each stage.

JC: It is a little too structured when you consider how life actually is, how it moves.

SH: Exactly. Niguma is saying, if you don’t understand it as illusion you are missing it. How do you approach this complex path to enlightenment from the viewpoint of illusion? I don’t know how present that view is in the Shangpa lineage, but it works for me.

JC: I am reminded of the Diamond Sutra where the Buddha uses many similes of illusion. It seems that Niguma was keeping the Buddha’s view alive in her teaching.

SH: Yes, for the Buddha, his Prajnaparamita teachings have been personified as the feminine. Niguma gave me a way to relate to the path literature.

More about the book . . .

Providing a rare glimpse of feminine Buddhist history, Niguma, Lady of Illusion brings to the forefront the life and teachings of a mysterious eleventh-century Kashmiri woman who became the source of a major Tibetan Buddhist practice lineage. More than an historical presentation, Niguma’s story challenges the view that images of accomplished female practitioners are merely symbolic representations of the « feminine principle. » In some cases they portray real spiritual leaders. This volume includes the thirteen works that have been attributed to Niguma in the Tibetan Buddhist canon. These collected works form the basis of an ancient lineage, Shangpa, which continues to be actively studied and practiced today. These works include the source verses for such esoteric practices as the Six Yogas, the Great Seal, and the Chakrasamvara and Hevajra tantric practices that are widespread in Tibetan traditions.

« Such an important historical female figure as Niguma has been obscured by centuries of overlaid mythology, but now Sarah Harding has skillfully managed to separate the wheat from the chaff and reveal something of the woman behind the legend, along with her place in the Shangpa tradition and her fascinating writings on Yoga. »

—Jetsunma Tenzin Palmo, author of Reflections on a Mountain Lake«

Niguma is Niguma. A book is a book. If you read with discernment, however, and put what is written into practice, you just might meet Niguma face to face. »

—Yangsi Kalu Rinpoche

« Sarah Harding’s fascinating account of the literature surrounding Niguma, heiress of unimaginable qualities, provides a rare glimpse into the life of a legendary female practitioner who traces the source of her wisdom lineage directly to Vajradhara, the epitome of awakening. The collected works and biography are gems of insight into the spiritual journey of this elusive figure whose realization culminates in the perfection of timeless awareness and an illusory rainbow body.

« Deftly written, the account is a treasure trove of information about tantric practices and attainments, focused especially on the nature and power of illusion. Harding’s attempts to separate the flesh-and-blood woman from the idealized dakini makes for an engaging, often amusing read for neophytes and experienced practitioners alike. Of special relevance to those who happen to be women this time around. »

—Karma Lekshe Tsomo, editor of Buddhism through American Women’s Eyes

« The elusive « Lady of Illusion » Niguma was the eleventh century female founder of the tantric practice lineage that forms the central core of the Shangpa Kargyu tradition. For many years those of us interested in Niguma’s teachings have been waiting for this book. Now, thanks to the masterful translation work of Sarah Harding, we have it. And though we still may not know the specific details of Niguma’s life, what we are given here—through these personal, detailed and distinctive practice instructions—is the unmistaken reason for her enduring legacy. Kudos to Sarah Harding for making this unique treasure-trove available. »

—Jan Willis, author of Dreaming Me

More about the author . . .

Sarah Harding has been a Tibetan Buddhist translator and practitioner since 1974. Her publications include Machik’s Complete Explanation. She has been on the faculty of Naropa University for nearly twenty years and lives in Boulder, Colorado.

Books by Sarah Harding

The Life and Revelations of Pema Linga (trans.)

Machik’s Complete Explanation (trans. and ed.)

Niguma, Lady of Illusion (trans. and ed.)

The Treasury of Knowledge, Book Eight, Part Four: Esoteric Instructions, A Detailed Presentation of the Process of Meditation in Vajrayana (trans. and annot.)

© 2010 Snow Lion: The Buddhist Magazine & Catalog