Akong Rinpoche acknowledges that you were the compassionate Mother, Tara, who had helped the lamas, when they had fled from Tibet. You had wept to see lamas forced to work in road gangs with other refugees in India. Moved by compassion, you had set up « The Young Lamas Home School, » at Dalhousie, where Tulkus and lamas could continue their religious training and learn English.

Akong Rinpoche recalled the occasion when as young men, he and Trungpa Rinpoche had come to the verandah of your house. The lamas, still in their teens, were dressed in robes. They pleaded for assistance. You surrendered completely. You took both lamas into your home and your heart. They were treated as sons. In return, you learn the inner aspects of Tantric practices. Your agile mind saw that the Tantric Teachings far surpassed the slower path of the Hinayana way.

You talk of the young Trungpa when in robes. The light that you had witnessed in the lama’s face. Celibacy, you explain, heightens compassion, and the energy to transmit teachings. Bodhicitta, sublimated sexuality is the means of this transmission. In your presence, I am constantly aware of your own vow of celibacy, and inner aspect that is blissful.

That evening, we watch on the television the wedding of Princess Anne and Captain Mark Philips. Since your ordination, you have seen no films. You are simply an elderly English woman moved by the pomp and ceremony of the occasion. Memories bound up in images of the Queen Mother, members of the Royal Family, and the beauty of Westminster Abbey, moved you to speak of your own English background.

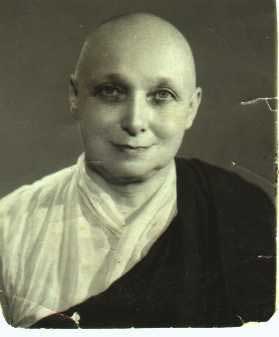

You, Sister Palmo, had been born in Derby, as Freda Houlston, in February, 1911. Your father, Francis Houlston, a merchant, died in battle in the First World War. You were brought up by your mother, Nellie Houlston, in the town of Derby. You attended the Parksfields Cedars School there. But your going up to Oxford changed your life. You helped a fellow scholar study for the entrance exam to Oxford. You made such progress that you too wrote the entrance exam. You unexpectedly were accepted, while the friend failed. A year of living in France with a French family prepared you somewhat for the experience of Oxford.

You went up to Oxford a provincial girl. You left it four years later as a determined radical thinker who had married a fellow student, an Indian, Baba Bedi. These years were so formative that you were already set upon a path that was characteristic of your future life. Two of the great minds of the century were to visit Oxford…and influence you. They were Mahatma Gandhi and Rabindranath Tagore.

Gandhi visited England and Oxford in 1931. You immediately came under the spell of the Mahatma. This was a religious leader who had evolved a humanism that went further than the Marxism or Socialism popular with your generation. The Ahimsa that Gandhi propagated was a spiritual path based on « correct insight » of the mind, and a « non-violence that aimed at ridding the personality of hate, passion and prejudice. » It was a culmination of Gandhi’s reappraisal of Hinduism and the writings of Tolstoy. Later, you came to understand this as an aspect of Buddhist meditation…the mind that is energetic in enquiry, and the practice of morality. In India, during the thirties, you became a Satyagraha, one who both believed and demonstrates the « firmness of truth ». This was the beginning of your long struggle for Indian Independence.

At Oxford you fell in love. The man was a fellow Indian student, Babajie Bedi, a direct descendent of Guru Nanak, a founder of the Sikh religion. You loved Babajie Bedi, and shocked your contemporaries by marrying an Asian. Your need to break with conservatism was strong. It had begun with your decision to leave the Anglican Church at the age of seventeen, and become a free thinker. Your union with Babajie Bedi, an Oxford Blue, was your first commitment to India, the land that would claim you.

You followed Gandhi, and were attached to the Socialist leader, and disciple of the Mahatma, Jayprakash Narayan. You were in those days of political involvement, a professor of English at Fateh Chand College in Lahore. The violence that occurred later before Indian Independence shocked you. It also gave you insight into political change. You understood this during your visit to South Africa in 1972. You sensed that apartheid, like all intolerable systems, would ultimately fail.

Rabindranath Tagore, the ageing and bearded prophet came to Oxford. He was, in contrast to the austere Gandhi, flamboyant and radiant. Tagore spoke about the power of poetry, of an age of spiritual revolution. Tagore had come as an emissary to the west long before the later influx of gurus and teachers. Dr.Diasetz T. Suzuki, Krishnamurti, Hindu swamis, Zen roshis and lamas. Tagore threw a gorgeous fabric before you, the images of the country which you would soon visit, India. You would travel there with your husband Babajie Bedi. You would leave Derby, the last vestiges of provincialism, and find fulfillment.

Tagore loved and respected Buddhism. He had written a play, called « Worship of the Dancing Girl. » Tagore had explored Buddhist legend. The play concerns Nati, a dancing girl, commanded by the King that she should dance before the sacred altar of the Buddha in order to desecrate it. Instead Nati dances a series of mudras of devotion. one by one, all the gorgeous wrappings of the dancing girl are put aside as she disrobes during the dance. Finally, Nati is left only in the ochre robe of the nun. Similarly, the outward trappings of your life, Sister Palmo, fell away. Like the dancing girl, Nati, you too are revealed in your essential nature of the nun.

Gandhi and Tagore both influence you at Oxford. Both minds were totally immersed in the new spirit of the age. Tagore was a man of poetry, who believed in the new humanity. Gandhi believed in the same humanity, but saw it transformed through action. Gandhi, you followed through the long political struggle. When Indian Independence came, you were exhausted. A spark had gone out with the assassination of Gandhi, and his cremation on the Ganges. You declined to enter Parliament as a minister. You renounced political life. Instead, you chose to work for the reconstruction of India. You strove to build something new from the ruins of British Imperialism. You turned to social work, Tagore, you kept in your heart. In your own life; you realized the essential vision of Nati, the dancing girl.

India possessed you. Like the Buddha, you had traversed all the holy places…the Four Sacred Shrines…Lumbini, the birthplace of the Buddha in Nepal; Buddhagaya, where the Buddha had attained enlightenment; Varanasi, the place where the Buddha had preached his first sermon to the five enlightened ascetics; and Kusinara, the place where the Buddha had passed into Parinirvana in Uttar Pradesh.

You recounted all of this at Akong Rinpoche’s home in Dumfries, as the images of Princess Anne and Captain Mark Philips faded on the television screen. You are that remarkable combination …a westerner, who is also deeply oriental, yet so subtly blended that it is impossible to sense any line of demarcation.

The train left Dumfries. We travel to Stirling, home of your niece, Mary. Ancient stone walls, rolling grass lands, and a cloud filled sky are in view. on the journey through Scotland, I am released from taking teachings within the confines of a meditation centre. I sense the person beneath the robe.

You explain that you had been both a politician and a Professor of English. Yet, you do not elaborate either on literature or politics. Your appetite for knowledge has fallen away. This had happened in India, when you had first gone up into the mountains to meditate. Since then, you have not kept up with the computer like flood of information over the past decade. Meditation, Buddhist philosophy and the encounter with others in the religious sense is your prime concern.

At Stirling, your niece meets us at the station. You embrace this young Englishwoman, and her small child with customary warmth. You are her aunt, the magical visitor from India. You have that mistique of the Victorian era, of relatives returning from the East, who become magnified, even exotic, in the minds of others. Yet, you are profoundly conscious of your English roots. Your brother, the father of Mary, was a submarine commander in the Second World War. He had been torpedoed off the coast of India. He had survived many hours in the water.

After his rescue at sea, he had been re-united with you in India. Apart from this encounter, you had been cut off from your English relatives for years. It was only now that during your travels as a meditation teacher that you were returned to your niece in Stirling, an old aunt still living in the Lake district. Your mother, Nellie Houlston had already died; and your brother too had collapsed after a coronary. It is hard for Mary, your niece, to understand that you had grown up in her familiar England. Yet, your many years in India have altered you. You are a person infused by other cultures, different conduits of information, and unique in being the westerner who is also genuinely of the East, as well.

Responding to your niece’s curiosity, and my own unspoken questions, you talk of the central experience of your life. This is your conversion to Buddhism that occurred in Burma. You had always been inclined to contemplation. In your school days, from the age of fourteen, you had meditated in the Anglican Church in Derby. Throughout your married life, you had found a period of solitude each day. Hinduism flourished about you in temples, works of art, the Indian way of life, and the yogis and sadhus. The Sikh religion was strong too, directly influenced by your husband, Babajie Bedi. Yet, none of this satisfied you. You read extensively into Christian and Sufi mysticism. Theresa of Avila, St. John of the Cross and the poems of Rumi moved you. Buddhism once strong in India at the time of the great Nalanda University, had been destroyed by Islamic invasion, centuries past. There were few books available at that time, either on the life of Buddha, or the practice of Buddhist oriented meditation.

You had reached the age of forty-three with your political career already behind you. As a social worker, an opportunity arose for you to join a United Nations mission to Burma. You arrived at Rangoon, and a country where Buddhism, in its present form, survives. You wander through the Golden Kioung monastery at Mandalay. The architecture, people, and a subtle atmosphere of Buddhism impress you. You view the great river, the Irrawaddy. You move into the interior of rugged hills and encounter crude peasants and artisans. You stand on the edge of vast forests with teak trees sometimes growing to a height of 120 feet.

But, more important, in Burma, you found a teacher of meditation. There was a monk who was prepared to instruct you. It was no easy task. Westerners did not learn meditation in those days of the early fifties. You had a struggle with the initial lessons. Later, when the Venerable Sayada U Thittilla Aggamahpandita taught you personally, you truly understood the nature of meditation. The Burmese monk gave you a warning. Even after initial instruction, a student often underwent an experience. This experience was not confined to the hours of sitting practice. It could, and did often happen in life itself.

Sister Palmo, you left for the hills on field work. Here, the experience about which the monk had warned, happened. A vision of a radiant lotus floating upon the sea, appeared before you. It was an experience of mystical intensity. Tears had poured down your face. The experience lasted several hours. The mechanical aspects of behavior still functioned. You continued to speak to peasant women; and made observations on agricultural problems. Your fellow social workers sensed that you were elsewhere. They had left you alone. Later, your associates gently assisted you to the village sleeping quarters. You had found the essence of what you had sought over the years. The transcendental experience, the unitive wisdom. The solitary hours spent in the Anglican Cathedral in Derby had been the beginning. Those early hours of first light in prison had continued the pattern of meditation. Moments too, in married life, when you had broken away from the physical embrace, to a moment of interior silence. You had realised the ultimate bliss. You were like those precious gurus of Tibetan mythology who are born in the heart of a lotus. Miraculous, such beings nurture humanity.

The United Nations project came to an end. You returned home to India. You told Babajie Bedi of the experience. You implied that you could no longer be a wife in the physical sense. The vision of the lotus had cauterised, even burnt away that aspect of your nature. You were now a bramacariya, one who has renounced sexual life. But you remained as mistress of your home, and mother to your children. India had for centuries seen men and women live in chastity together in the home.

As a Buddhist in India, you were isolated from your teacher in Burma…the Venerable U Thittila Aggamahpandita…a condition which was worsened when that country was closed for foreigners. You diligently practised the Hinayana/Theravada Path. But it was not easy to practice over the years without the closeness of a teacher, so necessary for progress on the path.

Apa Pant, the Indian diplomat, and a colleague of your political days, urged you to visit the Gyalwa Karmapa, head of the Kagyu sect of Tibetan Buddhism. The Gyalwa Karmapa had only recently arrived in India, had just fled from Tibet. Apa Pant had already been influenced by Tibetan Buddhism and had visited the great Tantric monasteries of Samye, Ganden, Sera and Drepung in Tibet itself.

The encounter with the Karmapa was as unexpected as the experience in Burma. You, Sister Palmo, then a deeply meditative woman of the Theravada tradition came humbly to meet a regal head of a sect of Tibetan Buddhism. The Karmapa, with warmth and compassion, and a mind plunged in a constant samadhi, greeted you. The meeting was veiled by intimations of grace waves. The East abounds in stories of those who after years of searching suddenly encounter the being, the saint incarnate in flesh, who is the oceanic in the power to ripen others. You knew immediately that this Tibetan Yogi was your guru. You, who had wandered so long, had now arrived home. You understood by mudra; the manner in which the hands of the Karmapa moved across the crystal mala. This was a mind to mind teaching. Words and philosophic dialect were unnecessary. A radiance such as that which you had known in Burma, was born in you again.

The Karmapa, on his part, had recognized a relationship with you over lifetimes. He immediately accepted you as a personal pupil. He initiated you, and prepared you for the Tantric path. You subsequently made many retreats upon tutelary deities of the Kagyu sect. You developed the profound sense of bodhicitta, the inexpressible clear mind realisation of the Buddhas.

You recall both the encounter in Burma, and your meeting with the Gyalwa Karmapa to your niece and myself as we sit in the livingroom of the house in Stirling. You teach not only from a highly disciplined training of the Theravada vehicle, but draw inspiration secretly from the visionary experience of Burma. In Stirling, I know your kindness as a meditation teacher. I labour with the details of the Tibetan Chakra system, and the complex visualisations of the tutelary deity of the mandala. You explain that through this intense path of form, the visualisation of the self as a deity, an inner transformation takes place. The pure and radiant mind emerges. You insist that I must find my own way, develop my own insights. Your knowledge remains mysteriously your own.

The Scottish November night is cold. Your niece makes me a bed on a sofa in the livingroom. You are distressed. You insist on lending me the outer portion of your robe for warmth. It is the self-same robe that I had once seen abandoned to the laundry in Cape Town. That robe had urged me to follow you to the mountain retreat in South Africa. Wrapped in this same robe, before sleep, I believe that I shall find you. Distant countries, and the isolation of your month long retreats can never cut you off.

Before sleep, I recall events of the life of the Buddha, Gautama, the prince had left the palace after witnessing the Four Signs…illness, old age, death and robed mendicant. The prince had cut off his long hair and donned the yellow robe of the mendicant. He became an ascetic, and practiced meditation and austerities.

Driven to despair at failing to find truth, the haggard prince, an emanation of privation, chose a spot beneath a Bodhi tree. He was determined not to rise from this chosen place until enlightenment had been reached. Forces of the unconscious assailed the royal mendicant. But Gautama crossed the barriers of ignorance, and the defilements inherent in human nature. The prince of the Sakya Clan, with a superhuman effort, abandoned all familiar territory of habitual mental processes, and won through to the state of enlightenment. He had severed the roots of desire. Karma, and all its entanglements were cut. There was no more re-birth. Buddha, was the muni, the one who had gone, utterly gone beyond.

The form of the Golden Buddha fills my dreams as I sleep beneath your robe. I stand on the thresholds of the places of meditation of the Buddha; mouths of caves; shade under the great Pepul tree; beside flowing streams.

At breakfast, I return the maroon outer robe to you, Sister Palmo, the rightful owner. The robe is your daily attire. A garment that is rough, worn and travel stained. It is essentially you, the bhikshuni, the intimations of Buddhahood hidden in the cloth.

The stay is Scotland is over. For me, it has been a time to get to know you as a person. But the power of the woman to move me in no way erases my powerful initial impression of the yogi. A farewell to your niece in Stirling, and a brief visit to Glasgow. Then homeward bound, for us both, on the Glasgow-London express.

As you prepare for sleep, you notice that I am restless, and wide awake. You gently explain to me something about the yoga of dreams as practised in Tibetan buddhism.

« The Yoga of dreams is a method of entering the dream state, and exploring it without waking. In this manner, the adept sees that dreams are as illusory as reality experienced when awake. Both states will be seen to be identical. This teaching is part of the Six Yogas of Naropa. But it is a fairly advanced teaching. The foundation practice must be completed first, before the study of the Six Yogas is undertaken. »

At Euston station, we drink early morning coffee on arrival. You are no longer the adept, or the teacher of philosophy making clear the essence of your study over the years with Khenpo Thrangu Rinpoche at Rumtek Monastery. Rather, you are an elderly woman, who has made a long overnight journey. The pallor of your face, and the lines of exhaustion about the eyes, remind me again of your frailty. Swiftly, I hire a taxi to take you to Indian relatives in Hampstead. They will have a comfortable room prepared for you on arrival. Travelling as your companion has enriched me beyond measure.

Next day I am in your presence. You are refreshed after the long journey. In the house in Hampstead, you are surrounded by flowers, fruit and incense. You suggest the insubstantial quality of Tara, the mother of compassion, in your gentle bearing. You observe that the dark forces of the unconscious that had threatened me at Samye Ling have been dispelled. You convince me that these forces can become transformed into creative energy. You then explain that you must leave shortly for India. The visit to England and Europe is over. You bless me formally. I know that soon you will be again at the Dharma Chakra Centre in Rumtek. You will be surrounded by distant snow-capped mountains, and the green rice valleys. It does not worry me that you will be far away. This is your place in time and space. There is the certainty of seeing you again. The Karmapa will be coming to the west, the following year. You will be in his party travelling as his translator. There is the assurance of the continuity of the teachings. It cannot be otherwise. You are the Lady of Realisation.

At the end of February, I return to Africa. In the cottage above the Indian ocean, I meditate before the shrine of reeds, shells and a Buddha Rupa. My life settles down to caring for a family, and writing. Your presence, Sister Palmo, is powerfully alive.

In a letter from Sikkim, later in the year, you inform me of the impending departure of the Karmapa and his party to the west. You are most certainly included in that auspicious group. I decide to join you in America.

I leave Johannesburg on a raw spring day. I arrive in New York in a blaze of autumn colour. I recall images of you, Sister Palmo, during my long flight; the nun in the silent house in Cape Town; the friend who lent me the bhikshuni’s robe in Scotland; the elderly woman pale with fatigue, after the rushing night train journey.

I join you in San Francisco, and check into a hotel in Berkeley. Barbara, your American devotee, gives me news of an initiation which the Karmapa will bestow the following morning. You insist that I attend the ceremony, and receive the blessings and empowerment of the Kagyu lineage. I know only my good fortune to be in California during this auspicious visit.

Next morning, I take a cab to an address in Berkeley where the initiation will be given. Zen students, Hindu devotees and students of Trungpa Rinpoche wait respectfully for the arrival of the Karmapa. At last, the Karmapa Lama appears, dressed in the maroon robe of the gelong. He is leaning upon the arm of Trungpa Rinpoche, who is dressed in the yellow robe. Both lamas enter the hall, and they are followed by the monks.

The signal is given for us to file into the hall. All are neophytes, and sit cross legged upon the floor. The Karmapa Lama is enthroned upon a golden dais. He is the Vajra Master, surrounded by ritual implements. We, the neophytes hold rice, a stick of incense or a flower, as an offering. The Karmapa chants the refuge and bodhisattva vows. The invocation of the universe follows, and the world is seen as the mandala of the guru. Specific dieties are invoked. The empowerment is then bestowed upon those present. The spontaneity of Mahamudra, the highest non dual meditation is the seed of this empowerment. Finally, the Karmapa shares the merit with all sentient beings.

The beauty of this moment, the Karmapa’s mudras, and the chanting of the monks cannot overshadow your precious form, Sister Palmo, silently in the background, yet so irrevocably part of this spiritual event.

After the initiation ceremony, I find you in the crowd. Sister Palmo, you emerge from a crowd of disciples, and embrace me with customary warmth: « I’m so glad that you managed to come to San Francisco. It is a great blessing to receive an initiation from His Holiness, Karmapa. But you must receive an audience with His Holiness as well. Come with me, let me take you to Him.

Students of Trungpa Rinpoche, drive us to the solid and impressive American style house in San Francisco where the Karmapa and monks are housed. Good as your promise, you insist that I be presented to the Karmapa together with the American poets. You are always conscious that I am a poet of Africa. Allen Ginsberg, Lawrence Ferlinghetti and Michael McClure are among the poets waiting to be received in audience by the Karmapa.

Together with Allen Ginsberg, I bow before the Karmapa. Without the dorje and bell, symbols of the Vajra Master, the Karmapa is a man of simplicity. Michael McClure, the west coast poet, presents the Karmapa with a delicate miniature of a bird in a glass case. The Karmapa holds up the case enclosing the bird, as if invoking it to find wings and fly. The intense gaze of the Karmapa possesses all the mystery of a great siddha.

Allen Ginsberg, with a full black beard, and gentle hands, addresses the Karmapa: « Does His Holiness recall my visit to Rumtek some years ago? Then, I had asked you whether the taking of LSD was a valid spiritual path. »

The Karmapa smiles, and shakes his head, and replies, through an interpreter: « The use of drugs creates an artificial sense of higher consciousness. Only mind in its natural state, a complete openness, the practice of mahamudra, achieves this. »

There is laughter in response to Allen Ginsberg’s question from the other beat poets, those who had progressed through the exploration of consciousness in the sixties. Lawrence Ferlinghetti sits in silence, like another Mahakashyo, the disciple of Buddha, who received a direct transmission by simply witnessing a gold flower in the hand of the Blessed One.

Aware of Africa, a world of harsh sunlight and rugged terrain, I ask the Karmapa for predictions for that land. This Guru, who had witnessed Tsurphu overrun by the Red Guard, replies:

« Suffering is inherent in life. Buddha is the remedy for suffering. Know that at some time the consciousness of a Buddha will awaken in Africa. »

The audience is over, and the Karmapa smiles a farewell blessing. We respectfully file out of the room. So much has passed through my mind that I am silent before you, Sister Palmo.

You gently insist that I return to my hotel. A young poet gives me a lift across the bridges that link San Francisco with Berkeley. In the quiet room at the hotel, I meditate upon so much that has happened. All this experience has the texture of a myth with strands that link Asia, Africa, and America.

The Karmapa performs the Black Crown Ceremony at Fort Mason. Throughout history, it has been the function of each Karmapa to perform this ceremony for the sake of all sentient beings. Whoever witnesses this ceremony will never again take rebirth in the realms of suffering. The fifth Karmapa, Teshin Shegpa, first wore the present Vajra Crown in the Fifteenth Century. This is the crown which is now in the possession of the present Gyalwa Karmapa. When Teshin Shegpa visited China, the Emperor Yung-Lo, a devout disciple, saw an invisible crown hovering above the head of Teshin Shegpa. Emperor Yung-Lo had a physical replica made of the miraculous crown which he had seen in a vision. The crown is still said to have the power of transmitting enlightenment on sight.

A throng of two thousand people from San Francisco fill the Fort Mason area. Again, the beautiful people come, with flowing robes, flowers, Indian shirts, colourful saris, long hair and beads. All have come for the great blessing of the Vajra Crown Ceremony.

The stage is set for the Ceremony, as monks sound the Tibetan horns. It is like a scene from a medieval pageant. The Karmapa mounts the dais. The monks bow, and present the precious box containing the heirloom, the Vajra crown. (A monk wears a cloth about his face, so that his breath will not disturb the ancient fabric.) The crown is placed upon the Karmapa’s head. The Karmapa prounounced a mantra: OM MANI PADME HUNG. The Karmapa enters a deep samadhi. He has assumed the attributes of Chenrezi, the Bodhisattva of compassion. A great energy of compassion fills the arena. The concentration of the crowd reaches a breaking point. Then as mysteriously as it had arisen, the tension is gone. Your face, Sister Palmo, watching this yogic feat, authenticates the veracity of my experience. The Karmapa, all smiles, blesses each individual with a precious relic from Tibet.

As I leave Fort Mason, I wonder how such a guru, the Karmapa, comes to pass like an ordinary person in American society. Comprehending the needs of the divided psyche of Western man, this guru has come to America bringing gifts such as the Vajra crown Ceremony. The yogi, whom I had witnessed in deep samadhi an hour ago, is also a skilled diplomat, and friend, who mingles with ordinary Americans in parks, museums and homes.

There is a reception for the Karmapa at a Japanese hotel. Then we go to an old house in San Francisco, on Capp Street, the home of Tamara Wasserman. The house is tastefully furnished. Thangkas frame the walls, and butterflies are preserved under glass. You rest on a sofa. I remain sitting cross legged upon a cushion on the floor. As you sleep, I sense the areas of your life which I can never penetrate; the yogi; the renunciation; your relationship with the Gyalwa Karmapa. These facts remain closed, unspoken even. You are deeply mysterious as a person, despite the outward simplicity of the Buddhist nun. Your profile in sleep has a softness. Wisdom emanates from your form like an ancient stone Buddha from the temples of Ceylon. You wake slowly like an insect fluttering from a cocoon into a world of light. We drink tea in Tamara’s kitchen. A breeze comes off the Pacific ocean. Later, you give teachings to those that come…Jose and Miriam Arguelles, Tamara, and others. You speak of the miraculous nature of the mind:

« Mind in its natural state is radiantly void. The sense of a permanent ego dims this inner light. The initiations and blessing which His Holiness Karmapa is giving purify the dross of ego. Abhisheka also means to wash, to purify. Through initiation, the vehicle of the body is made pure. The higher energies can be channelled into states of meditation. If there is effort, struggle with fundamentals such as kindness and generosity, then one is very much at the beginning of the path. Once the activity of the Bodhisattva energy begins to be activated, the flow of energy becomes subtle, direct and increasing. But at the beginning, there is the need for purification, and the blessing of the guru. »

After the discourse, you bless upon the head with a text of the words of the Buddha. Again, I travel across the bridges that link San Francisco to Berkeley. I re-examine the truth about which you had spoken. Images of the initiation, and the great humanity of the Karmapa move me to assimilate the truths about which you have expounded. Like a thief, I enter my own room at the hotel. I am divorced from my clothing, personal possessions and books. They no longer appear to belong to me. Your presence, Sister Palmo, has freed me, briefly, from my own sense of ego.

In the Shrine Room of the Nyingmapa Centre in Berkeley, the ancient school of Tibetan Buddhism established by Padmasambhava, the Karmapa bestows the Buddhist precepts. Before the ceremony, sister Palmo, you comment on the necessity of taking the precepts:

« Precepts are rooted in the Theravada tradition. They are the basic moral teachings of the Buddha. Precepts invite us to be true to ourselves. The first three precepts are concerned with killing, lying and stealing. The following two forbid adultery and the taking of liquor and drugs. Precepts form the basis of Dharma. »

The Karmapa graciously conducts the ceremony. Twelve of us, a mere handful who had attended the Crown Ceremony at Fort Mason, are the recipients of the blessing. You translate throughout the ceremony, and finally say: « His Holiness exhorts you to be happy. This is a joyous occasion. Morality is the basis of freedom. »

In the garden of the Nyingmapa Centre, you elaborate further on the implications of the Buddhist precepts: « We are all old warriors, who have lived many life times. We have inhabited the world of animals, fighting and quarreling, living only for the moment. We have passed into the state of hell beings, and the hungry ghosts suffering unremitting pangs of remorse. We have lived in the higher states of the gods, suffused in happiness. But even this joy has been incomplete.

Always we have been forced to take re-birth again and again. In this life, we have found a precious human body, and a mind capable of receiving the Buddha’s teachings. Precepts held up create wholesome karma. They are the foundation of holistic living. They create a unity within the personality. We are no longer in conflict with the self. A calm mind naturally arises. »

You give this discourse, with the Pacific ocean a distant rumble. Your words echo from the past; they are ancient. The core of these Teachings was propagated by Lord Buddha centuries earlier.

Sister Palmo, you are a rich presence in the San Mateo garden. You are at peace beside the stone buddha at the rockery. Barbara, a close devotee, is the decorator and landscape gardener. A hidden premonition prepared her to take trouble over the years with the house and garden knowing that you, the Lady of Realisation, would live and teach here. You emanate great happiness. The Karmapa has been warmly received in America. Many have received the blessing of the precious guru. You are fulfilled. In the garden, I recall aspects of your life.

You surely possessed this same radiance when you had entertained princes and politicians in your Kashmir home. The saris, which you had worn, flowers in your hair, and the glamour, which you had possessed, were all put aside. You had perceived an elusive vision, which was hard to realise. You understood the truth underlying reality. You understood that the constructions people place upon events and circumstances is born of ignorance. Reality, truly observed, is devoid of association. Existence, purified of emotional attitudes, is radiantly pure.

You withdrew from the world. You took the ordination of a Buddhist nun. From that moment onwards, you dressed in a robe. Unresolved conflicts, disturbing emotions and ignorance were severed through meditation. Until your sixtieth birthday, you were cut off, meditating in the mountains, exploring the shoals of the mind. You reached a resolution, a conviction best interpreted as bodhicitta, the enlightened motivation to help others. Having understood profound mysteries, you could lead others to the source.

There are moments in the garden at San Mateo when I sense the past. The writers shine through clearly in the texts of beauty which you have translated into English from the original Tibetan. The social worker emerges in the practical assistance you give to the young. Nothing deters you. Problems of drugs, sex and alienation are understood. The Buddha is the remedy for suffering. I never think of you as old. You are timeless, accessible and deeply intuitive. You have in those years of retreat at Rumtek monastery come to terms with impermanence, sense of a permanent ego, and death. These subjects, the classical meditation of the Buddha, are not dry and remote. You make them facts of life for all to study.

You understand meditation. You have travelled the path from concentration and insight to Samadhi. You have completed the stages of Mahamudra meditation. The subtle insights bestowed by dieties such as the Green Tara and the Vajra Yogini are secret to you alone.

Yet you are more than a teacher of meditation. You are a symbol of renewal. I know that by your act of returning from the mountains, that you believe in humanity. Somehow goodness can prevail. The energy crisis, pollution, and terrorism, are only the familiar furies of history appearing in new guises. You have progressed beyond these painful dualities. You propound a realisation beyond good and evil. You learnt that during those years of retreat at Rumtek Monastery. This is the reason why you have come back. You, Sister Palmo, are marvelously intact. You represent the indestructibility of the pure mind. With you gone, I recall this valour in all its immaculate purity. I seek it, relentless, in my own nature.

In the morning you are on the way to Vancouver together with the Karmapa and monks. I gave you a promise that I would meet you in Toronto soon. The following day, roaring engines take me back to Kennedy airport. My strands of karma with you, Lady of Realisation, are already intermingled. Another pattern is emerging. A few short weeks and I will be again re-united with you, Sister Palmo.

Some weeks later, arriving at dusk at Toronto airport, I take a cab to Bodhisattva House, a Buddhist centre. You had left a message there telling me that you had gone ahead to Bellville where a Tibetan settlement had invited the Karmapa to perform the Vajra Crown Ceremony. You suggest that I join you there. A group of young Tibetans give me a lift to Bellville. These Asian teen-agers, now settled in Canada, have adopted a western lifestyle. Like nominal catholics, they know only the outward trappings of Tibetan Buddhism. They invoke the Bodhisattva, Chenrezi, and show respect to the Dalai Lama, and the Karmapa. But they look with humour at myself who attempts to meditate seriously.

At Bellville, I find you staying at a motel together with the Karmapa and party of monks. You simply accept that I have arrived safely. Sometimes I imagine that you and the Karmapa are like a magic show that might simply vanish into thin air! Yet here in this comfortable motel, you are flesh and substantiality. You have been reading the books of Carlos Castenada. You comment that the lore of the Indian sorcerer, Don Juan, can be interpreted in the Tibetan esoteric teachings. You compare the power of Don Juan to the Tibetan adepts able to create tulpas, a projected thought form which takes the human shape. These tulpas can be created and dissolved at will. Though you point out that the energy of a tulpa can become dangerous if the adept is not the complete master of his own projection. The idea of the tulpa is the same as the western concept of the « doppelganger », the replica of the real person. You insist that you have to keep up with some reading in order to answer the questions put to you by young Americans.

I bring a small Buddha rupa, a genuine Tibetan artifact, that bears the authentic seal of origin, for the Karmapa to bless. You immediately arrange an audience. You usher me into the presence of the guru. The Karmapa rests in a comfortable chair. I present a white scarf and prostrate three times, the customary protocol, before the head of a Tibetan sect of Buddhism.

The Karmapa, face wreathed in smiles, breathes life into the Buddha rupa. Quite simply, I know that I have come as a westerner, as naturally to this great guru, as any peasant had come centuries earlier to an ancient Karmapa in the past of Tibet.

In the morning, a slow train takes us to Montreal. You sit in the lotus posture on the train seat. I make you comfortable with a blanket and pillows. Turning from the bleak landscape, I question you about meditation. You speak of the arising of the bodhicitta, the enlightened processes of the Six Yogas of Naropa. I sense your power as an adept.

Mike and Ebba Breacher meet us at the Montreal station. You had met them on their honeymoon in Kashmir over twenty years ago. You had been Freda Bedi then, and it was shortly before you had gone to Burma and embraced Buddhism. They show no surprise at the robe, shaven head, and spare profile. You are still Freda, the magical woman of Kashmir. Mike and Ebba sense your preciousness. You had been a good omen on their honeymoon Then Mike had been a colleague, a lecturer in political science in Fateh Chand College in Srinagar. Ebba, new to India, and imbued with a fierce Hebraic quality, had thrived on her friendship with you.

In the Montreal apartment, you recall life in India. You speak of Pandit Nehru. Your children had called this statesman « Uncle » and Indira Gandhi, his daughter, was your comrade in the political struggle. Somehow the robe which you now wear fails to obscure the woman whom you had once been. Freda Bedi is never diminished by Sister Palmo. Freda had travelled across India, made speeches from political platforms inspiring women of all classes…untouchables, peasants and illiterates. Sister Palmo has travelled across Europe, Africa and America, bringing a different message of hope.

There is an ease in which you have returned to Mike and Ebba Breacher though years have passed. You are again that mysterious traveller who has made the journey to the East. You have returned with a treasure, the innate purity of your own nature. A mind that shines with such a radiance that reflects those images of political and academic life in Kashmir, and yet remains silent at the centre. Here in the company of old friends, you revisit the past. Images of marriage, children, Nehru’s profile, the deprivation of weeks in prison, appear before you. 0thers might have found these memories drenched with emotion. Through your mastery of Mahamudra meditation, such images are seen as radiantly empty. They appear as phantoms of the past.

You, Sister Palmo, acknowledge and recognise your old life. Yet, it has no power to move you to regret or sorrow. You had come up to 0xford a provincial English girl. There, you had encountered Gandhi and Tagore. A handsome Sikh, Babaji Bedi, had claimed you, and brought you to India as his wife. In middle life, you saw political strife, and encountered spirituality in Burma. Later, you became the pupil of the Gyalwa Karmapa, and finally took the renunciation of the Buddhist nun, bearing the name Karma Khechog Palmo. All are different textures of experience. The veils have been removed one by one, like Tagore’s dancing girl, Nati. Now, you wear the final garment, the maroon robe of the Bhikshuni.

Returning to Toronto, you are anxious to attend an Ecumenical Congress which is being held in the city. Catholic and Protestant clergy mingle with the representatives of the Buddhist, Hindu and Sikh faiths. The atmosphere is one of co-operation. Sister Catherine, a contemplative nun of the Redemptrist order, is the guest speaker. Sister Catherine, aged about fifty, has put aside the nun’s habit and dressed in tailored slacks and cashmere sweater. A silver cross about her neck, a severe hair style, are the singular signs of her renunciation. She possesses a deep contemplative wisdom, together with a strong philosophic mind. She has spent the last number of years involved in Buddhist dialogue in Asia. She recalls the silence of the great stone Buddha at Polonnaruwa, in Ceylon. A silence that had filled her with the startling evidence of the reality of the void as described in Buddhist Sutras.

After listening to Sister Catherine’s talk, you tell me that if you had not been a Buddhist, if karma had not brought you to India, you could certainly have found comfort in the contemplative orders of the Christian Church. Sister Catherine embodies for you the Christian ideal which includes aspects of Buddhist wisdom. Thomas Merton believed that it was this blending of Buddhism that could leaven Christianity in the west. Like Thomas Merton, you too are a bridge between East and West. You have fulfilled a unique role in the development of Buddhism in the west. It was through your endeavours that the young lamas who had fled Tibet were housed in the Young Lamas Home School at Dalhousie, which you had established. It is through your constant inspiration that the Karmapa has made this historic visit to America. Now, you teach western students the foundations of Buddhist practice.

In your approach to teaching Buddhism, you remember that most western students possess either a Christian or Jewish background. But despite this early conditioning, you never limited instruction in the Dharma to fit into comfortable categories. You explained that taking the Refuge in the Buddha is a total commitment, a single-minded path. You made clear too the fact that westerners practice the monastic path of Tibetan Buddhism. This practice goes far beyond the nominal faith of the average Tibetan who invokes the mantra of Chenrezi, and gives respect to the Karmapa. The westerner practices the arduous foundation path, the cornerstone of the Tantric Path of the Four Sects of Tibetan Buddhism. This foundation Path includes meditation upon Precious human birth, impermanence, karma, and suffering. Then comes the taking of the Refuge in the Buddha, the engendering of compassion, prostrations, the practice of Vajra Sattva Purification meditation, and guru yoga.

I recall Tantric images, seen in pictures, engraved upon the rocks of Tibet; red stained outlines of the Vajra Yogini; dark forms of Padmasambhava; and the immaculate white Chenrezi. Ancient forms that are still symbols of the psychic renewal of man. All move me to an understanding of the insubstantiality of the world.

We drive up to Kinmount, a country meditation centre. We pass through Fennelon Falls, having left behind us the wintry landscape of Toronto. on the journey, you speak of the conversion of Yasa, a rich young man, who had encountered the Buddha in the Deer Park. Upon hearing the Discourse of the Blessed one, the immaculate and stainless mind arose in him. Yasa immediately begged the Buddha to allow him to make the renunciation. This acceptance of Yasa by the Blessed one was the first formal ordination. It was only after the Fourth Buddhist Council in Ceylon, about 80 B.C. that the teachings of the Buddha were collected in the Tripitaka. The Vinaya, the disciplinary rules of conduct for the Sangha, were later committed to writing. During the Buddha’s lifetime, the communities of monks and nuns were well established. Such a ripening has occurred in three western women about to be ordained as nuns at Kinmount. Sister Palmo, the perfect bikshuni, you are anxious to witness the ceremony.

The ordination Ceremony is conducted privately in the Shrine Room presided over by the Karmapa, and attended by only the monks and yourself. After the ceremony the new nuns emerge. They stand awkward in the winter sunlight, shifting new robes about their bodies, and feeling with frozen fingers their newly shaved heads. Later, in the cabin, you share with an elderly nun, you explain:

« The requisite for a Buddhist nun is not necessarily a mastery of meditation. It is rather an ability to live a special kind of life. A woman who wishes to become a nun should examine her motive carefully. She should be able to live alone, no longer desire men, and abstain from alcohol. The vocation of a nun is more « dependent upon a lifestyle than control of the mind. »

Anna, a newly ordained nun impresses me. She is a nurse by profession, and already in her late forties. She tells me that she had visited Cape Town, trying to be a settler there, close to a married daughter. The atmosphere of racial tension, and that strange society, had not been able to accommodate her. Driven by a spiritual need, she had visited India and come to see the ashram of Swami Muktananda. Here, the Karmapa was paying a courtesy visit. Seeing the Karmapa, and receiving His darshan, she understood that her quest was over. The Karmapa accepted her, and advised her to take further teachings. Two years later, she had travelled to Kinmount, for her ordination as a nun.

Sister Palmo, you are a Mother in Dharma. You are a help to the new nuns in a hundred different ways. You advise on the cutting of robes; the rules of conduct; and meditation practice. You repeat the injunction given by the Blessed One, one Century earlier: « Go forth, monks, and teach the truth, which is glorious in the beginning, the middle, and the end, for the good of all beings. There are some whose eyes are not obscured by dust. Teach them, they will understand. »

At Kinmount, I sit a moment with you. I try and explain what it has meant for me, both meeting and travelling with you. You sense the question that shyness prevents me from asking: « What people experience in meditation is not attributed to the powers of the guru. Bliss and radiance occur of themselves when the mind is tranquil. They are elements within the mind of the meditator. »

I wait in silence beside you, happy to be in the presence that inspires such warmth, and contains the hidden elements of wisdom.

Our journey, next day, is through the darkness of a Canadian November evening. The monks, together with us, chant the Mahakala puja. I listen to the praises of these protective deities. The Mahakalas usually ride a mule. They carry a bag of poison which kills the enemies of the teachings, which hangs from their saddle bags. They possess too a mirror of judgement and a snake lasso, and a bow and arrows. The Mahakalas remove all obstacles to the growth and practice of Dharma.

Beyond the window of the Combi, I sense the landscape and trees. Further across oceans and continents, lies Africa. The Karmapa, the monks, and yourself leave soon for Samye Ling in Scotland. I shall lose you soon. I must return to Africa, where my daughter in a boarding school patiently waits my return. My responsibilities crowd in. These few days have seen me severed from my ordinary life. For a brief spell, I have fallen within the mandala of the Karmapa.

There is a final initiation at Bodhisattva House in Toronto. In the crowded shrine room, I find a place behind the newly ordained nun, Anna. The seductive pealing of the bell, and the eloquent mudras of the Karmapa, fail to distract my attention from small scars on the head of the new nun. I recall how Anna had been shaved with the help of students at Kinmount. The harshness of life is symbolised in those small scars. Between the mudra of the Karmapa, and Anna’s scarred head, exists different worlds. Suffering and my desire for transcendence overwhelm me. I turn towards you, Sister Palmo. Yet your head is bowed in a total acceptance. You have gone beyond the rugged terrain of the dualities. You have reconciled the opposites. You do not put constructions upon such observations. You have awakened from the slumber of ignorance. All that arises in the mind is spontaneously pure.

That night I dream of you, sister Palmo, in the form of the Vajra Yogini. You wear a crown of dried skulls, a necklace of severed heads. You carry a skull cup full of blood, and a hooked knife. A trident leans against your shoulder. In the morning, you give teachings. I sense the essence of the yidam in your own nature. You judge my progress. You understand my difficulties. You admit that the meditation text which I had been studying for three years is difficult. Yet you stress that the detailed visualisation of a deity, colours and ornaments, is there to exhaust the mind. It is a process similar to that used in the Zen teachings. After the mind is exhausted comes a blow from heaven. Realisation is often sudden.

Your departure is at hand. Sister Palmo, you are certain of our next meeting. It cannot be otherwise. Lady of Realisation, you are so certain of your powerful grasp upon life.

I had returned from America to my family in Africa. You, Sister Palmo, in contrast are travelling in the party of the Karmapa through the European winter of 1974. You are visiting the capital cities of Europe. In Rome, Pope Paul receives the Gyalwa Karmapa in private audience. You have a sense of the dialogue begun by Thomas Merton continuing in the presence of the Karmapa at St. Peters. From Denmark, you write of the enthusiasm of the hippie community for the lineage teachings. Marpa, the translator, and Milarepa, the poet and yogi, truly live for Scandinavian youth.

From Amsterdam, you write in answer to my letters that have followed you across Europe: « …..so many earthquaking and glorious things have happened and we are travelling on the good earth, and not in the sky. Glory be! Kosmos, and the Theosophical-Vedanta setting have made Holland interesting. Now we wait for the web of many colours called Paris. Dear, love and blessing of the Three Jewels. …. »

Months pass on these travels. Later, Barbara writes that you have had a heavy bout of the flu. She has seen that you rest in the Paris Hilton Hotel. The crowds, the northern winter, and the monotony of vegetarian food, have taken their toll. You are no longer young, but a woman in the early sixties. Sister Palmo, you have always driven yourself hard in the service of others. Hearing this news of your fatigue, I am reminded of the weary letters of Swami Vivekananda, written at the turn of the century.

A letter, written to Mary Hale, from Vivekananda, reflects the exhaustion that spiritual teachers surely suffer today: « Now I am longing for rest. Hope I will get some, and the Indian people will give me up. How I would like to become dumb for some years and not talk at all. »

In May, 1975, the long tour ends. You who have visited continents, witnessed foreign cities, and encountered thousands of faces in this grand cavalcade of Dharma, now go into a retreat.

You write on arrival at Rumtek: « My retreat begins in a few days time, and there are piles of mail, things to study, to write. One month. The birds sing. We all feel happy to be home, and His Holiness is well. So am I. In the grace waves of the guru-lama…. » You make your retreat upon the Chagchen Mahamudra. Your mind is understood as arising spontaneously – natural, free. There is no effort on your part; all is without meaning. You remain constantly in the natural self-nature of the mind.

Two years pass before we meet again. You write from Rumtek Monastery, and give news. The Indian ocean stretching between Africa and India, keeps us apart. Yet your presence is still felt in my world.

From Rumtek you write: « His Holiness is well, and all’s right with the world. Today one of our Incarnates, aged about 14, left for Ladakh and it was quite moving to see him leave the scene of his childhood. He will be trained to take charge of Kagydupa monks there….. »

Travelling to Bombay in September, you write: « The first hint of Spring in this winter atmosphere. Everything is within the good black earth, and not even a hint of a shoot, green or otherwise shows the way to release…but in the refuge of the Triple Gem, we understand, our labours…..

In November, writing again from Rumtek: (You also refer to the possibility of my joining you in California in1976.) « …..the comforting feeling that we shall be able to meet in California next year…if that is in the stars and planets whirling in the great Cosmic Sky Mandala. once his Holiness had an interview with a woman who had come by jet all the way from South America to see him. She had an impossibly difficult married life to an older man. His Holiness gave her one of his radiant smiles, and said: « When things are at their worst say, « Thanks to the Guru » and you will understand. »

In February of the following year you had been on a visit to Nepal. You had again been a member of the Karmapa’s party. The tour had been a special visit to the monastery in where the Karmapa had given a series of high initiations.

You wrote of this event: « His Holiness is a golden glowing Chenrezi Padmapani. Nepal was a saga of which I shall speak to you personally. The Monkey Temple at Swayambunath moves me more than Bodh Gaya which is old and wonderful too. The country of the Buddha; it has some transcendental quality of otherness and « nowness » too.

The extraordinary patterning of karma does indeed bring me to California. My flight across the Poles is exhausting. Yet I am convinced that I must spend this time with you; live out the California Spring. You are the guru; the one who can impart the seed of Buddhahood. I recognise this fact. What had begun in the summer lit room in Cape Town five years ago will continue in the house in San Mateo.

I am again in your presence in America. Time has stood still. Sister Palmo, you fill the room with a great translucence. There is a terrible knowledge too. A heart ailment has been diagnosed. You are ill. I know this at first glance. The warmth of your embrace is drenched with a poignancy. A sense of time running out. There is no certainty that I shall find you again. Each morning I come to your room, and receive a blessing. You are the embodiment of Tara, the Vajra Yogini, and the other deities of the mandala. I know no self consciousness in bowing before you.

At the Asian Institute, you give discourses. You reflect insights of your years of study, and also your own mystical experience of Burma. A woman pandit, you address jean-clad America. You discuss enlightenment and all its profound implications. You consider the psychological leap; the supreme logic; the brave bodhisattva; all are elements of Buddhahood. You advise each student to meditate for himself. Certain realisations are the fruit of intuition.

Despite a heavy schedule of interviews and lectures, you always preside at the luncheon table. You possess the palate of a yogi – demanding, changeable, and subtle. Sometimes you desire a spare vegetable dish. Another time, it is pork chops, or shrimps. Visitors come to lunch – Alan Ginsberg, Claudio Naranjo, and Buddhist scholar, Stephen Beyer. You talk of philosophy, family life and culture. You are a good listener, yet, you seldom laugh. Your insights into impermanence and death have not lead you to the « joking » realisations of the Zen Masters. Perhaps this is because you are also an Englishwoman of an earlier and more conservative generation. After lunch, you rest in the garden, peaceful among the blue jays and flowering shrubs.

There are many accomplished woman yogis in the history of the Vajrayana. Tibetan Buddhism abounds in female deities, dakinis and consorts of Buddhas and bodhisattvas. This feminine energy represents the principle of openness, and a cutting through the confusion of mind. Historically too, the woman yogi is of great importance. Niguma, who lived in the eleventh century, was an accomplished woman siddha. She was in early life the wife of the Mahasiddha Naropa, who later renounced the householder’s life and became a monk. Niguma too followed the path of Renunciation. She mastered Tantric teachings, and became renowned for her magical attainments. With this background, of a long tradition of woman siddhas, and yogis, it did not seem incongruous that Sister Palmo, you bestow an inner initiation of the Kagyu lineage.

The text of the initiation speaks of the samsaric nature of existence, and the skilful means to transcend suffering. As the Vajra Master, you welcome us into the mandala and crown each of us as your equals in Dharma. At this stage of the initiation, which deals with purification, you hand us two reeds of kusa grass. You explain your reason for this.: « Put the long reed under your body, and the short one beneath the pillow when you sleep tonight. The power of the initiation will cause dreams of a symbolic nature to occur. »

Following your instructions, I place the reeds in the manner in which you suggested, on retiring. I immediately fall into a deep sleep and experience three different dreams. In the morning, I encounter you in your room, maroon clad in the robe of the bhikshuni.

I explain the first dream; how I had simply found myself in an ancient Indian temple garden, a place of perfect peace. You merely nod, and are silent about this dream.

The second dream had been more in the nature of a nightmare, which I recount: « there was a terrible weight, a dark figure upon my chest, crushing life out of my body. It was both terrifying and threatening…. »

You interrupt my recounting of the nightmare and remark: « The dark figure symbolises purification. This is not an uncommon dream. It is a good sign of impurity coming away. Think of delusion leaving you forever. Ignorance and fear cannot sway you again. »

The third dream is more difficult to recount, for it involves you, Sister Palmo, appearing in an inner form. « In the third dream, I am witness in Africa to terrible battles, and turmoil. You, Sister Palmo, appear in the form of a white yogini. You wear a white robe, and possess upstanding hair. Your visage is fearful. You wear a necklace of skulls about your neck and brandish a trident. You pacify the hordes of darkness. »

I did not know it then, but when I returned to Africa, all the unleashed violence of the Soweto riots had broken out. You admit that the vision of the white yogini is yourself but in an inner form. You are silent about this emanation of your mystical presence in my dream. There are aspects of the yogi about you that manifest in extraordinary ways. You have a power to emanate and teach on inner levels. You are without doubt an accomplished yogi, in the long tradition of woman siddhas going back to the all powerful saint, Niguma.

Sakyamuni Buddha, in his earthly life, studied medicine in the forests of India. Tibetan Buddhism has elaborated further, and transformed him into a blue celestial Buddha of Medicine. Sangyes Menla, who appears in a lapis lazuli colour, and wears the three Dharma robes. He holds in his hand the Trimphala Amla fruit.

Sister Palmo, you too possessed an insight into healing. You had encouraged the nuns at the Tilokpur Monastery to learn the preparation of herbal remedies under the instruction of a lama. Often, you could sense an illness either physical or psychological in a student, and suggest a remedy. You always advocate that healing is a full time study and occupation. You encourage students to pray to Sangyes Menla, the Buddha of Medicine. At San Mateo, you perform a special healing Buddha Puja, and distribute blessed pills to the sick.

Later in the garden, you talk with elderly Major and Mrs. Knight. you speak about Dharamsala, and the presence of the Dalai Lama, whom you honour and revere. Major and Mrs. Knight have lived many years in India, and have given support to exiled lamas. You did not realise it then, that only a week later, Major Knight would die of a heart attack. When you heard this news later, at the breakfast table, you said:

« It is no great sadness to die in old age. Easier to leave life in good health. Why suffer, if when karma is worked out, the thread of life snaps. Major Knight had lead a good life. We cannot shun the inevitable. Death comes to all. »

You take up the vigil beside Major Knight’s body. You conduct the Phowa prayers. The aggregates that had left the physical body now make the journey to the bardo realm. You console Mrs. Knight. Your vigil beside the body is of a classical simplicity. I recall your visit to South Africa, when you had been called upon to perform the Buddhist funeral prayers at the cremation of a Chinese seaman who had been murdered in a dockside brawl over a prostitute. You had seen beyond the sordid aspects of the man’s death, and rather perceived his radiant essence. An extraordinary woman from India, Sister Palmo, you had come to Africa in order to guide a seaman through the realms of the bardo night. Africa and Asia met in you in an unusual interweaving. Now, you are linked with Major Knight, and again perform the ancient rite for the newly dead.

During this memorable week, you talk to an enclosed order of Carmelite nuns. The nuns are dark shapes, behind grilles, who listen intently to your lecture. You speak about Buddhist meditation, and life at Rumtek Monastery. You explain how Buddhists meditate alone in a cell. This had been the method in Tibet, when yogis had inhabited caves, and monks have sought out isolated hermitages. Buddhists like Christians come together for prayers or as in the case of Buddhists, for the celebration of puja. Yet, I know from my discussion with you that the Buddhist sects have in their discipline rich aspects of yoga. It is the energy of passion, transmuted and controlled, that forms the basis of realisation. Such insights are surely not intrusive upon these women, Carmelite nuns, dedicated, like yourself, to a life of the spirit.

In California, you spoke often of Trungpa Rinpoche. As a youth Trungpa had come to your home in India, together with Akong Rinpoche. Both lamas had begged your assistance. Like a mother, you took them as sons into your own home. Later, you arranged for a scholarship to Oxford for the young Trungpa. In those early years, Trungpa had possessed a radiant purity. But now you understand that the Lama had taken on Western karma, and taught in the manner of a siddhic teacher. The Karmapa on his visit had called Trungpa Rinpoche the Padmasambhava of the West.

Trungpa Rinpoche, dignified in a tailored suit, receives you in a house in Berkeley. The lama greets you in a formal fashion – the head blessing customary between a guru and disciple. You had brought a text of a Mahamudra translation for the Rinpoche’s comments. Conversation is between old friends. The Lama speaks of the coming visit to the Karmapa to America in the winter. He talks too of his own intention to make a year long retreat.

Trungpa Rinpoche sees in you, Sister Palmo, the generous woman who had helped him in India. He senses too the depth of the yogi within you. He had helped to bring these powers fruition. The Rinpoche recalls that he had not dared give the Phowa teachings for fear that you might not have returned to your body. He new the exquisite delicacy of your insights; the deftness of your manipulation of the veins and the airs of the Six Yogas of Naropa.

On this afternoon in Berkeley, the Rinpoche is totally at ease; the links between you both span fifteen years. You possess the same Vajra energy, and an integrity that makes the efforts of ordinary people seem strained in comparison.

Later, when I had returned to Africa, Barbara writes that Trungpa Rinpoche had come to bless the Shrine Room at San Mateo. on this occasion, the lama had changed the lineage prayers of Karma Pakshi. Sister Palmo, you had knelt in contemplation in the shrine room. The Rinpoche had turned to you, and remarked: »I shall not see you again. But after the passing of time, we shall be re-united. »

A look of compassion shadowed the Rinpoche’s face and gave a sudden presentiment of your passing.

From Africa, I had written earlier in the year requesting the Green Tara Initiation from your hands. Here, in the California Spring, you confer this empowerment, the authority to meditate upon the green and lovely form of Tara.

During the initiation, you instruct me not to see your physical aspect as a Buddhist nun, the composed woman of sixty-five, but I must instead concentrate upon you in the form of Green Tara, a sixteen year old virgin girl, bejewelled and blossoming in youthful vigour.

I enter the shrine room, and prostrate before you. The altar is piled high with offerings, flaming candles, and an image of the Buddha. I see you in the form of the radiant Goddess, Green Tara.

Before you bestow the initiation, you say: « Every teacher, before giving an empowerment must speak of their authority and competence to do so. I have heard His Holiness, the Dalai Lama, speak very humbly of his own attainment before a great initiation that he was about to have given in India. The Dalai Lama was humble and modest as is any great lama. It is hard for me, with this in mind, to present my own accomplishments. Simply believe that I have the authority, and the ability, to bestow this initiation. »

The reformer, Atisha, and Marpa, the translator, are among the ancient lineage holders of this initiation which has come down through the line of Karmapa Lamas. As the ceremony progresses, you finally place the torma of initiation upon my head. At that moment, I see myself as the embodiment of Green Tara; she is both a reflection of yourself, and the deity beyond. This insight is one of the deep mysteries of Tibetan Buddhism, the knowledge that Tara is both a creation of mind, and a real deity.

In the Shrine Room, I meditate upon the beauty of this peaceful empowerment Tara’s tranquillity is about your presence, Sister Palmo. It suffuses the Shrine Room, and makes those who have received the initiation aware of a centre of peace within their own hearts. Yet, even at this moment, I sense the poignancy. I must leave you again. I no longer have the certainty of finding you once more. Your life energy is diminishing.

Shortly before I leave, you receive me formally in the sitting room. In the robe of the Mahayana nun, you indicate the territory of shunyata, which the meditator will encounter in practice.

« The experience of shunyata shakes the foundation of one’s being. But you must not despair. For a period, emptiness in the sense of living in a world without concepts, name and form, overtakes one. there is a sense of total aloneness, even meaninglessness. Students suffer intensely. Yet, it is essential to the path. All the practice of meditation upon form, sadhana, and empowerments lead only to this realisation. If we do not experience shunyata, then all the teachings of the Buddha remain dry discourses. »

I listen intently. I recall your experience in Burma, the warning given by the Thai monk; the vision of the lotus upon the sea; how your life was irrevocably altered.

You continue to speak about the problems inherent in the practice of meditation: « Meditation is never easy. Even with myself, it has been hard. Babajie allowed me simply to remain at home when as a lay woman I felt shattered, or unable to take upon the practicalities of daily life. Meditation means coming to terms with one’s own energies. »

I sense the rightness of your insight, and know from my own fragmented self just how delicate the energies of the subtler realms are.

« Recently, I received empowerments from His Holiness the Dalai Lama that had left me withdrawn. I felt removed from life. His Holiness Karmapa encouraged me rather to return to daily activities, and give up on the long hours of sitting practice. He urged me to practice Mahamudra, the awareness of life itself. You will discover this for yourself along the path. »

This last profound advice is the final instruction that you give me. In retrospect, the essence remains. Now with you gone, this injunction still sustains me.

It is fitting that on the evening of my departure, Barbara plans a program of Tibetan music and mantra chanting. Sensing my departure soon, I feel the need to pay a special tribute to you. Barbara and I find the originals of the original Gelongma Palmo in a text, which you had translated into English.

This ancient text speaks of Gelongma Palmo, who is a woman saint of remarkable siddhic powers, dwelling in the forest hermitages of India. Barbara reads this tribute to you, Sister Palmo, before the presentation of Tibetan music in the Shrine Room: « The biography of the original Gelongma Palmo (known in Sanskrit as the Bhikshuni Srimati) who lived in the eighth century in India still exists.

« One should imagine the form of a woman with the yellow robe who lived in a hermitage, following the path of the yogi, dwelling in a forest, living a life of seclusion and meditation. We should not forget the powerful energies of Buddhism of that period. This was the time of the great Nalanda University, and the writings of the sublime poetry of Santideva.

The biography tells us in its spare fashion that the Gelongma Palmo showed herself in her outer form as the Bhikshuni, wearing the yellow dharma robe, with an uhsnisha mound upon her head, like the Buddha.

In her inner form, she manifested as Tara in green colour, removing all obstacles and hindrances. Thinking of Gelongma Palmo, in this form, we should recollect the very beautiful initiation of the Green Mother, which we experienced this morning.

In her secret form, the Gelongma Palmo appeared as a siddha, one who possesses miraculous powers. The story tells us that she appeared in the form of a siddha, cutting off her head, and put it on the trident of Guru Padmasambhava.

It is enough to see the Gelongma Palmo as one who had embodied a triple identity – the outer form of the woman in the yellow robe, the nun who had taken the renunciation, the inner form as an emanation of Green Tara, and the secret form of the siddha, the one of magical attainment.

The Gelongma Palmo reached the Tenth stage of the Bodhisattvas when the natural, « the simultaneously arising of the mind » occurred, in its nature very pure, the understanding of the Dharmakaya is clear. The nature of thoughts are utterly pure, clear and transparent. The Gelongma Palmo possessed the Sambhogakaya body of celestial bliss.

All this happened in the heart centre of Bodh Gaya centuries ago, and where pilgrims still flock to the holy places of the Buddha. »

You, Sister Palmo, of the twentieth century are moved at our insights into your pure nature. You are indeed an emanation of the ancient siddha, Gelongma Palmo, who dwelt in the forests of India. I follow the reading of the biography of the original Gelongma Palmo, with your translation of her outpouring of praises, the hymn to the bodhisattva, Chenrezi.

The following lyric hymn to Chenrezi was composed by the Gelongma Palmo as an outpouring of praise. What is the nature of such praise? Most modern poetry is about people with blunted sensibilities and heavy samsaric experience. Little today is understood about an outpouring of praise. We have to retrace our steps back in time to those who did understand such an outpouring of the heart – Rumi, the great Sufi poet and sage, and St. John of the Cross…. »

Then follows the hymn to Chenrezi :

« Om, Protector of the Universe, I bow down.

Praise him, lama of the Universe and the Three Spheres,

Praise him, the King of the Gods and Mara and Brahma

Praised by the Sakyamuni, supreme among Jinas, giver of realisations. …. »

You, sister Palmo, listen to the rendering of the hymn to Chenrezi. It is the outpouring of your own great heart. You too know the ecstasy of St. John of the Cross, the heightened bliss of the Sufi poets. All this joy overflows from the hymn to Chenrezi, the glorious bodhisattva of compassion. As if an echo to all this, a bearded youth, chants with a deep resonance of sound, the Mani mantra. You acknowledge our tribute to you with a wordless recognition. We have penetrated your heart’s essence.

Next morning, before my departure, you receive me. You are simply Sister Palmo, the woman who has taken the ordination, and wears the robe of the nun. You are formal, and place a traditional white scarf about my neck, and bestow the « head blessing », a bond shared between guru and disciple. The warmth of your brow amazes. How can I ever doubt that this life energy might cease! Then I leave your presence for the last time.

On my return to Africa, I am moved by Barbara’s letters from Mount Shasta, which describe a retreat you made on the slopes of that ancient mount, revered by the American Indian. Here at the foot of Mountain Shasta, a non active volcano, 14,000 feet high, you completed a two week retreat. Attended by Barbara, and your Tibetan nun, Pema Zangmo, you spend the days in meditation. The cry of coyotes, changing winds and the gusting of trees does not disturb. The mind remains natural, beyond the dualities. The territory of formless Mahamudra meditation.

Sister Palmo, you emerge from the retreat with a radiancy. You possess the mien of a wise and powerful deity. You have achieved an insight which is far from empirical thought. A deeply intuitive insight of the unity of nature, and the acceptance of impermanence and death.

Returning to San Mateo, you celebrate the tenth anniversary of your ordination as a Buddhist Nun. A decade earlier, you had on ordination adopted the name Karma Khechog Palmo. You wore the maroon robe of the Bhikshuni for the first time. You went about shaven headed. With a fierce devotional energy, you had worked for the welfare of Lamas, and the bringing of Tibetan Buddhism to the West. Now, in the garden at San Mateo, you look back on those eventful years. Many come to the anniversary celebrations. Musicians play in the garden. There is an anniversary cake with ten burning candles, one for each year of your saga as a nun. old friends in America, new young students, Allen Ginsberg and Lama Karma Thinley, of Toronto come to wish you well and great happiness. I who am far from you that day send you a letter in which I try and speak of the meaning of your ordination to me in my own life:

My Dear Mummy:

I would wish very much to be in your presence during the celebration of your Renunciation. As this is not possible, I shall simply meditate at my own shrine.

In my own life, I see with clarity the three poisons – greed, ignorance and hatred, the feelings which sway both the mind and the emotions. The only release is to cease from suffering in the manner in which the Buddha discovered it for all. The natural outcome of such thoughts is the taking of the Renunciation or the Going Forth. Surely, the Renunciation is not only the relinquishing of attachment and craving, but also the reaching out towards a greater compassion and emotional maturity.

In reading the life of the Buddha, I find again and again this phrase. Here it is repeated as when Yasa, the young man, said to the Buddha:« Lord, I wish to receive the going forth and the Full Admission of the Blessed one. » « Come Bhikku, » the Blessed one said: « The Law is well proclaimed. Lead the holy life for the complete end of suffering. »

This is the great simplicity, which is found, when all else has been exhausted.

When the Blessed one spoke to Yasa, and others, the phrase repeatedly recurs:« …the spotless, immaculate vision of the Dhamma rose up in him. »

I wonder what is meant by that immaculate vision of the Dhamma. Is it the thought that urges one to enlightenment? Is it the essence of bodhicitta, the Buddha nature? These are words that suggest complex intellectual stirrings. But in essence, I think that the « spotless, immaculate vision » does not refer to a vision of life that is purely intellectual. Rather, it is an innate understanding of original mind, the radiant void.

These are my thoughts on this day of your perfect Renunciation. There is nothing material that I can offer since all material things are exhausted and subject to change… »

My letter does reach you on that anniversary day in California. Your reply, Sister Palmo, arrives some weeks later. You continue on your journey – first to New York, and then make an unexpected trip to your son, Kabir, who is filming in South America. After this detour, you cross the Atlantic for a brief two days in London.

Finally, when you do return to India, in September, you write from Calcutta: »….your beautiful anniversary letter, and the poem that is deep and meaningful, as well as the book, « The Life of the Buddha« …..just the cool water of Dharma, I was looking for….reached me. All treasures. This is the true meaning of His Holiness Karmapa’ Guruji’s stress on Triyana Dharmachakra. Without the Golden Buddha and the sutras, the very foundation of Tibetan Buddhism is missing. »

« I am truly happy that you have found it all….and I know in my heart that this is a sign for you one day, hopefully in this life itself, there will be a Rabjung or Going Forth, when your family responsibilities are fulfilled…. »